The massive pedagogical transitions that the pandemic has forced, and continues to require, in all levels of education has elicited many discussions regarding the role of technology in the classroom, the best use of Learning Management Systems, and the ability to deliver our subject matters in online and hybrid environments. It is at the same time true that, as Omicron continues to send many universities online, there is a wide consensus in many schools that in-person and residential education continues to be the preferred model from traditional college students. At the same time, it is essential to recognize that many of the phenomena that have become magnified in the course of the pandemic belong to processes that have been unfolding for years. In the case of humanities education, the students demonstrate an increasing lack of ability to read books and other forms of lengthy writing, a perfect storm resulting from the gutting of humanities education in the name of STEM-centric and vocational agendas, the attacks against the humanities on political grounds and the rapid changes in the attention economy elicited by social media. One could moralize a lot about this, but I believe that there is a matter-of-fact problem in regards to providing humanities formation both using new technologies and cognitive conditions as our allies, and in understanding the ways in which we can continue to deliver traditional forms of literary education against the grain of current challenges.

In this blog entry, I discuss a pedagogical exercise that I have developed since the pandemic began: a book club. This is, of course, a bit of a counterintuitive exercise, as it pushes forward a traditional skill, book reading, that is increasingly scarce in education and that oftentimes feels contrary to the educational needs of students who are distracted, struggling and better suited to active than to passive forms of learning. And yet, as I have unfolded this exercise in my classes, I have learned a lot about my teaching, and the possibilities of teaching through books. I hope these notes help other professors and colleagues in thinking through these problems.

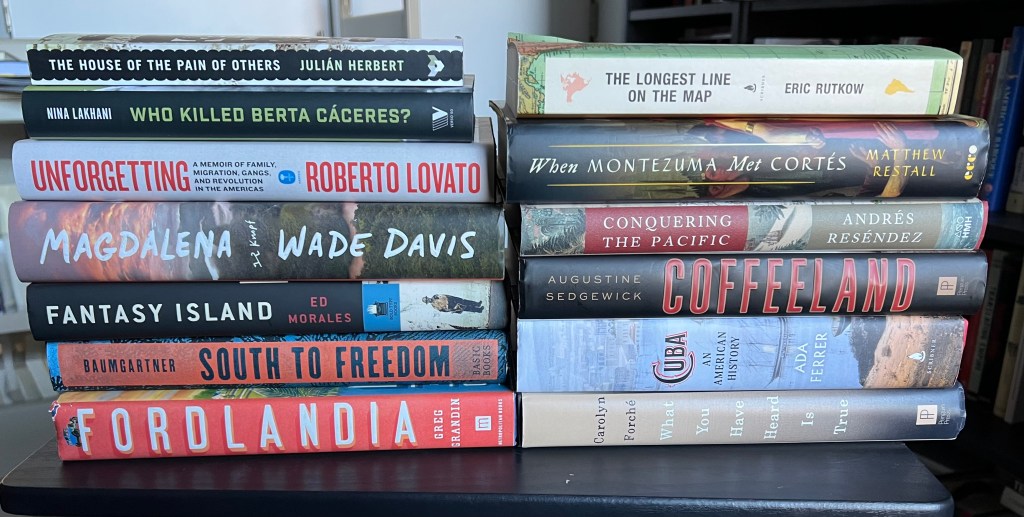

Every fall semester, I teach a course entitled Latin America: Nation, Ethnicity and Social Conflict, which serves as gateway for majors and minors in Latin American Studies, and often has students from the program in Global Studies, students looking to learn about the region before study abroad and Latinx students seeking to learn about their heritage. The class has 65 students or so per year, which makes it challenging in terms of truly addressing the diversity of students while creating manageable grading loads. During the fall of 2020, I introduced the book club in its fully developed form for the first time. I gave students books for their choosing, and each book could be chosen by no more than five students. But I believe that in the Fall of 2021 this exercise worked better after providing clearer guidelines based on the previous year. These were the available choices for Fall 2021:

I used a series of criteria flexibly. Due to the variety of prior knowledge in the students, I decided trade books were better (academic books may be too complex). They had to be fairly recent (only Grandin’s is older than five years). I should have read it in full before and enjoyed it (I am now buying this kind of book on the regular to have options for the future). They should somehow connect with topics studied in class (sometimes specific regions, other times conceptual questions). It is absolutely possible to swap these for academic books or for works of literature (in 2020 I used a novel by Edwidge Danticat, which the group enjoyed, but I found out they had a much different experience with fiction). It is conceivable to do this exercise with films too, but I think a different setup may be required to do so.

This assignment required each student to read their assigned book, which they chose at least five weeks in advance of the first deadline. This led to two assignments. First, I asked them to record a one-hour conversation with their group on Zoom and post it into Canvas. They were explicitly instructed three significant things: 1. This is not a class presentation and they could not divide the book up. Rather all of them had to read the book in full. 2. They could coordinate topics of conversation in advance, but the conversation had to be naturally flowing, rather than taking individual turns. Any prep other than reading the book and taking notes was discouraged. 3. All of them had to speak a roughly equivalent number of minutes, as the groups were graded collectively. After they turn this in, I asked them to write a short (5-7 pages) final paper with no secondary bibliography reflecting on their individual experience reading the book.

The reason why I arrived at this assignment has to do with a variety of concerns I have had in educating students in a class like this. The class is not in a literature program and thusly it is not always the expectation of students to read books. As a stalwart for book reading, I have taught this class in the past requiring full books, but over time this has become impossible. Students who have gone through reforms such as No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top, coming ever more from educational systems that appear to center STEM in a way that seriously undermines humanities educations, and the clear effects that social media has had in their attention span have affected their reading ability. So the class these days is taught with articles the first part of the semester, and gradually transitions to documentaries (which is a factor of the availability of quality materials, but does help students continue to be plugged into the class after midterms). I also know that, even though our institutional guidelines suggest 9 hours of homework a week for a 3-credit class, that students are overcommitted. In my elite institution, this means students drown themselves in extracurriculars, which means they often do their homework really late. And, of course, in most institutions (just like some of my own students), a good group of student often works to make ends meet.

In this landscape, book reading has become very challenging as a class requirement. The reality is that many underclassmen did not acquire the skill of reading a book critically and productively in their K-12 years, which is something that is not their fault, but rather a damaging omission inflicted one them. The book club is designed to allow the students to learn to read books building on the knowledge they develop over the semester, and in dialogue with their classmates.

I was very happy with the results. Except for one student who was not participative (out of 63 who completed) and decided to write a longer final paper instead, and a student who had to drop out due to health issues, every single one of the students was engaged with the book and the conversation. I would unhesitatingly say that this is the exercise that has yielded the most even output from a class in 15 years.

There were many things that I noticed in the groups. Students with Latin American and Latinx heritage often chose books close to that heritage. This meant that they both were a resource for their classmates in explaining to them their experiences, while at the same time clearly enjoying the opportunity to discuss it with new audiences. I also noted that students who had been intimidated by class participation in person were very comfortable talking to students in this setting (I would note that one of the requests I received for future teaching was using small groups more, undoubtedly a consequence of this exercise). The level of detail in which they read the book was truly stunning, nearly all students were able to point to specific pages in the book. They also were able to correct doubts and misunderstandings with each other.

As for the papers, I encouraged them to do a few things other classes do not. I encourage first-person writing, personal opinions and being critical of the books. This created really pleasurable papers to read. I did not get the noncommittal and even robotic writing that students can produce whenever they are perfunctorily completing assignments. A lot of the papers were very successful in bringing relevant materials from early in the semester to match their writing. Some papers were very moving in terms of students reflecting on questions about their identity and their understanding of political issues in their community. I prefer to not single out students to protect their confidentiality, but some individual papers were really moving.

There were many positive elements that I attested. Many students expressed shock and outrage regarding the fact that they did not learn Latin American history or even a basic history of US involvement in Latin America. Others found it productive to confront their heritages with their reading, or to reassess their experience in Latin America through their books. Many were able to move beyond simplistic ideas about the identity of the author and their purported privilege, to really understand what the book contributed to the understanding of Latin America, even when the author was not Latin American. And I believe it is important to note that the majority of students who did a course evaluation listed this assignment as their favorite.

There are a variety of permutations I have imagined of this exercise, and that I hope to put forward in the future. I think the exercise can be done with the purpose of multiplying knowledge in a class. For example, divide a smaller class in four groups and ask them to present their books in class so the rest of the class can get a sense of four books rather than just one (it would be conceivable to ask the class to read excerpts of the three books on which they are not presenting). I also think that one can develop an exercise in which the rest of the class watches the conversations of groups and comments on them. It would be imaginable to form groups, provide them some guidelines and ask them to pick books without a pre-determined choice from the instructor. In second-language classrooms, one could request more successive outputs: conversations with groups, followed by presentations for the class, followed by writing assignment. The written assignment can be designed to be in specific formats such as a magazine article. Students could also make more creative things: book trailers, multimedia engagements of the books, further research departing from the book.

At the end of the day, I am happy that this provides me a pathway to teach students to value book reading, and to read books with care. I hope this is impactful to some of them, particularly as many of them are stolen from the opportunity to read books by our increasingly anti-intellectual education systems.